lt’s no secret that today’s students are more stressed than ever.

Experiencing high levels of stress can be problematic, especially for students who experience test anxiety or are tempted to procrastinate when they get overwhelmed.

On the other hand, too little stress can also be a problem for students. It is not uncommon for a single student to vacillate between periods of too little stress— when projects and studying fall by the wayside—and periods of excessive stress—where they feel overwhelmed by how much there is to do and how little time they have left to complete it.

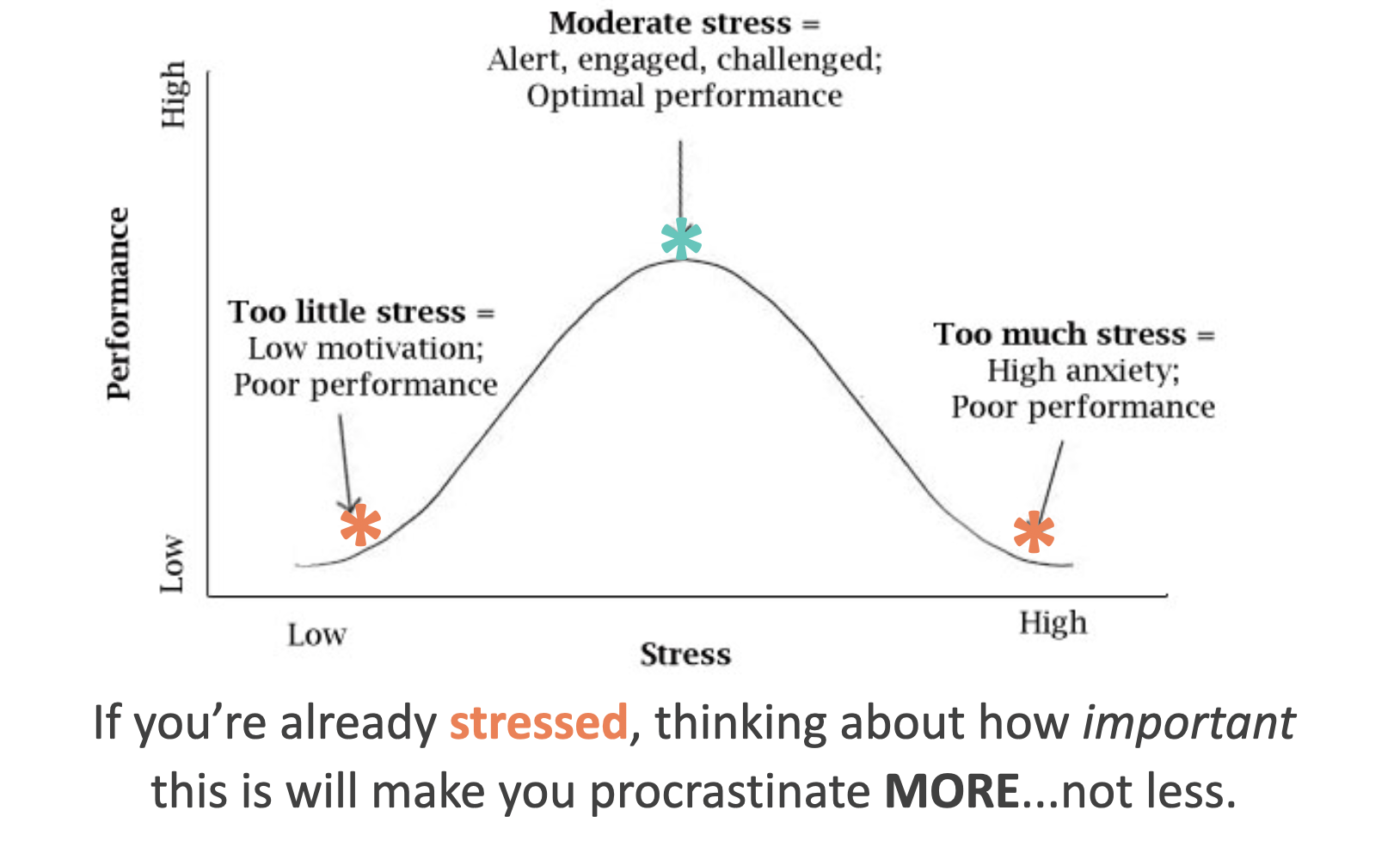

I’ve found that the stress-performance curve (i.e., “Yerkes–Dodson law”) is a useful visual model to use when explaining this concept to our students, because it enables them to see how stress is impacting their ability to perform at their best.

As the curve shows so clearly, neither stress extreme is going to create optimal results. For example, imagine a student who is so distressed by an exam that they leave the room in tears… clearly, they are going to perform very poorly on that test. Similarly, if a student was experiencing so little stress during an exam that they put their head down on the desk and fell asleep, this would lead to a very poor outcome. Regardless of whether your student’s level of stress is too low or too high, moving their level of stress closer to the optimum can help increase their performance on exams and assignments.

Creating an optimum level of stress:

First, your student needs to be able to assess their current stress level, and recognize whether it is too high or low. Once your student understands the link between stress & performance, they can check in with themself periodically and ask, “Where am I on the stress curve right now?” Depending on your student’s maturity and level of self-awareness, this may be a straightforward question, or something that requires some deeper thought. You can also help prompt this self-reflection process by occasionally checking in with your student about their stress level (“where do you think you are on the stress curve?”)

Once they’ve identified where they are on the curve, the next step is to actively lower — or raise — their level of stress to be closer to the optimum level for performance. Some students will already have some ideas about how to do this. If they still draw a blank even after prompting, here are some ideas to consider sharing with them:

For REDUCING stress:

- Decatastrophize. It can sometimes help stressed-out students to pause and ask themselves: “What’s the worst-case scenario, if this doesn’t go the way I’m hoping?” “If that really happened, what options would I have for how to respond? How would I handle it?” For many students, thinking through the worst case scenario can help them gain some valuable perspective on the situation and realize that it’s actually not as stressful as they’d thought. Then, they can shift to focusing on what they can do to improve their chances of creating a more positive outcome.

- Lower the bar. Sometimes, a student’s stress levels are high because they have set high expectations for their work. Instead of trying to do a GOOD job, it can be less daunting to lower their standards and start by creating a first-draft version that they can go back and fix later. Rather than worrying about the whole project, focusing on just taking the easiest first step can help lower students’ stress levels.

- Use breathing and/or physical relaxation techniques. Taking several deep “belly” breaths, performing 4-4-4-4 breathing (in 4, hold 4, out 4, hold 4), or just taking 1 or 2 slow, deep breaths can do a lot to reduce stress. Tensing all of your muscles and then slowly relaxing them is also a great way to quickly release stress. If there is more time available, exercise and meditation are other great options for relieving stress.

- Write about the stressful event. For students with test anxiety, researchers have shown that taking 10 minutes to write about their feelings before a test can improve their performance by nearly a letter grade (B- vs. B+). For more tips on reducing test anxiety, see our post here.

For INCREASING stress:

- Consider the impact. Sometimes students have a hard time seeing the long-term consequences of their actions. Encouraging them to think through the results of a decision can increase its perceived importance. For example, if your student realizes that choosing to play a video game now means they will: stay up late to finish their homework…feel tired the next day…do worse on their math test…end up with a B- in the class…have a lower GPA…have future options available for where to go to college…and so on, then playing that one video game can start to seem less appealing. Rather than telling your student the consequences YOU think will result from their decisions, try asking them about what they think the results will be each step of the way. The goal here is to help them develop the ability to connect current behaviors with future results.

- Help your student consider the emotional reasons why doing well (and/or avoiding doing badly) is important to them. If your student isn’t motivated, logic won’t do much to change that. Establishing an emotional connection to the results they do and don’t want is much more powerful. You can help your student make this emotional connection by encouraging them to talk about how great they will feel after they put in the effort, accomplish the work, and achieve a fabulous result…or how awful they will feel afterward if they don’t put in much effort and end up with a bad outcome. (As with putting it in context, it will be much more effective to ask your student how they will feel about the alternative outcomes, rather than telling them how you think they will feel.)

- Get specific about the time requirements. Sometimes students feel very little stress about studying for tests, or long-term projects, because they don’t have a good sense of how much time it will take, or how much time they have left. If this is the case for your student, then it may be helpful to brainstorm a list of all the steps that are needed to complete this work, estimate the amount of time each of these steps will take to complete, and calculate the number of days (or hours) that they have left to work, and then think about how much time is realistic to spend on this work each day. When we do this with our coaching students, they are often surprised by how many steps are involved in completing a project, and how little time they actually have to finish it. For an unmotivated student, this can provide a helpful dose of stress to inspire them to take action.

- Ask them about the effects that their behavior will have on other people. For example, if they don’t complete their assignment, they’ll have to go see their teacher after school and won’t be able to ride home with their friend. Considering how this might make their friend feel may be more motivating for them than thinking about their own personal consequences. Sometimes students will do more for their friends or their teachers than they will for themselves.

Results

It may take some effort for students to get to the point where they are able to identify and shift their stress level to different points on the curve, but it can pay big dividends. For many students (myself included!), their tendency is to feel too little stress in the beginning stages of a study plan or a project, but too much stress toward the end (or on exam day).

If they can develop the ability to actively increase their levels of stress during the days and weeks leading up to the test or the project due date, and then lower their stress during the exam itself, this can make a big difference in their performance.

In addition to helping improve students’ performance on exams, this exercise also develops some very important life skills. Making this bigger-picture shift in their perspective and developing the ability to mentally “step” back, assess their own emotional state, and then consciously choose whether or not to change it, is an executive functioning skill called “metacognition.” This skill is a critical component of emotional intelligence, which numerous studies have shown are strongly linked to students’ achievement and their success as adults.

Action steps

- Consider showing the Yerkes–Dodson diagram to your student and getting their thoughts about where they tend to fall on the curve. What are the situations in which they often find themselves falling too far to the right? Too far to the left?

- Help your student brainstorm ideas for things they can do to shift their stress level higher or lower. If they are stuck, present a couple of the ideas listed above as potential options to consider. Try following your suggestion with a question: “What do YOU think of that idea?” to emphasize that this is a choice, not a requirement. If your student isn’t crazy about the idea you proposed, ask what they think would work better for them. Once you’ve gotten them started, your student may have several ideas that are an even better fit for them than the ones listed here!

Join 11,000+ parents helping their students earn better grades with less stress!

About The Author

Dr. Maggie Wray is a certified ADHD Coach & Academic Life Coach with a Ph.D. in Neurobiology and Behavior from Cornell and a Bachelor’s degree in Astrophysics from Princeton. She founded Creating Positive Futures in 2012 to help high school and college students learn how to earn better grades with less stress. Her team of dedicated coaches is on a mission to empower students to develop the mindset, organization, time management, and study skills they need to achieve their goals.

Related Posts

Other Posts You May Enjoy

How Does Your Teen Handle Failure?

How do you feel about failure?Most of us aren’t crazy about it. But at some point, no matter how hard we try, we’re going to fail at something. So, it’s important to consider how to respond to failure when it does happen, and how to improve our resilience so we’re...

Optimistic students earn better grades

Is your student more of an optimist, or a pessimist? Studies have shown that optimists experience a number of benefits later in life, as compared with their more pessimistic peers, including… Better test scores and higher GPAs Lower levels of stress, anxiety, and...

Starting before you’re motivated

Most students want to do well in school. But wanting to do well doesn't guarantee they will feel motivated to work on assignments in the moment. Even students who usually get good grades have days when they just don’t feel like doing homework or studying for their...